Discovering Pierre Kwenders’s Pan-African Pop

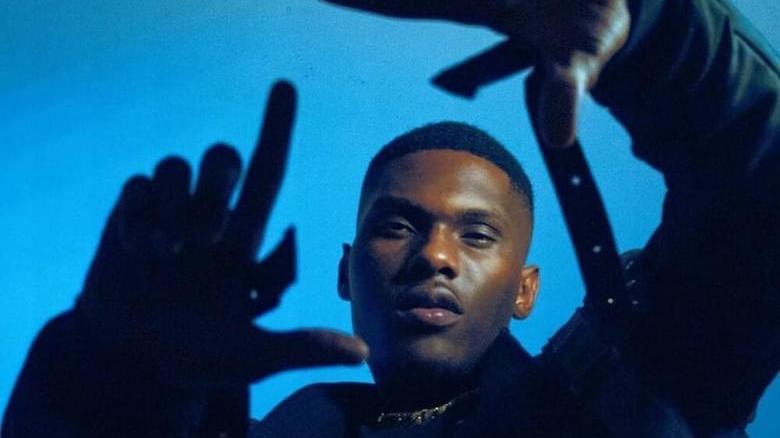

Pierre Kwenders—born José Louis Modabi—has one of the most excellent press photos you’ll see this year. What looks like a cool and calculated shot of him relaxing on a rug with a lustrous poodle companion was actually a lucky coincidence. “We were at the photo shoot, and another photographer came in with his dog, and I was like, ‘Can I get the dog in the picture?’ And he said, ‘Yes, she loves to be in pictures.’ So she came and sat down next to me and that was it.”

As soon as he saw his muse walk into the room, the Congolese Montreal native who takes his stage name from his grandfather, knew he could make an even bigger splash with a dog like that next to him. “I think it was just meant to be,” he says with a laugh. “I was trying to make some old-school R&B album cover pose like Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson, and this dog walked in, and I thought, ‘What a beautiful dog.’ Luckily the photographer was nice enough to let us use his dog.”

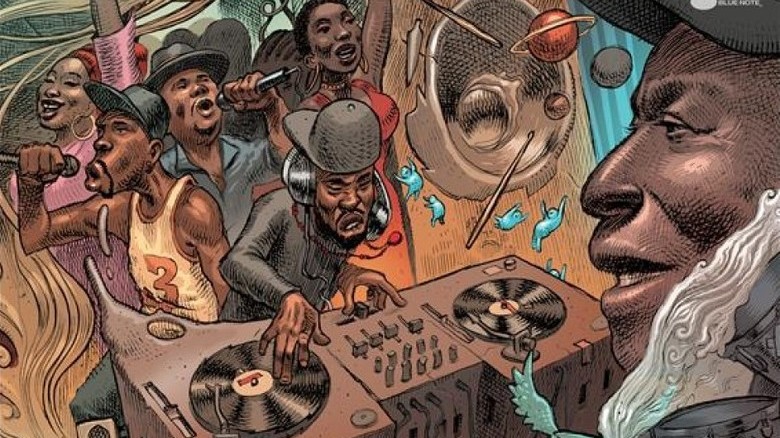

An album like Kwenders’s sophomore effort, MAKANDA at the End of Space, the Beginning of Time, deserves such extravagant imagery. Recorded in Seattle during whatever spare time Kwenders could find with his producer, Tendai Maraire of Shabazz Palaces, MAKANDA is a multilingual, multicultural blast of Afro-futuristic electronic funk, R&B, and pop. We spoke with Kwenders while he was driving around Montreal (speaking hands-free, of course) to discuss the importance of the women in his life, the pitfalls of being labeled “world music,” and how he is currently living the African dream.

You’ve called yourself ‘the spokesman of modern Africa’ who is ‘living the African dream.’ What do you mean by that?

[Laughs] Wow, that’s a good question. You’re the first person to ever ask me that. ‘The spokesman of modern Africa,’ not to be pretentious, but I believe I am like one of those young, African diaspor[ic people] that is showing a new image we don’t normally see. Within my music I try to showcase that. I use a lot of traditional music from my country in order for people to be more open and discover things from Africa. When I say I’m living the African dream, I mean that as a reference to when people here succeed after struggling, they say they’re ‘living the American dream.’ It’s just for me to tell people that it’s not only an American dream, it can also be an African dream. My dream was to make music after struggling, and today people are recognizing my art, which is great. So, I’m still living that dream.

Is that also why you describe your music as Pan-African?

Yeah, the idea behind this album was to create a sound for everybody. I wanted to make music that speaks to people from here but also people that left their country like I did. I want those people to be able to identify themselves in my music, but also people like yourself, so you can feel more connected to Africa in a way that you never thought possible before. I want people to be able to discover Africa but also Canada, because at the end of the day I’m Congolese, but I’m also Canadian. There is a strong influence from Quebec, from Montreal. The main objective is to create a bridge between those cultures that seem so far away, but bringing them together can make a beautiful thing. That’s why I use the term Pan-African. It’s not just a term for Africans.

I know you don’t want your music to be classified as ‘world music.’ How do you avoid being pigeonholed like that? Can you?

I believe it’s basically impossible to avoid it. We live in a society where people like to put everything in boxes, and it’s impossible to get out of it. You can go to the market and buy my CD, but if you want to find it you have to go to the world music section. Even though I don’t consider what I do world music. I feel that my music has no boundaries. We all use the same notes, and the only thing that changes is the context and culture. In the world music category, you will find a musician from India, some part of Africa, China, South America… it doesn’t make any sense. And if something is in English or French it’s considered pop or rock ‘n’ roll. But you get rock ‘n’ roll sung in Spanish and it’s considered world music. C’mon guys, it doesn’t make any sense!

What section would you want to be placed in?

What I do, I do it for the people. It’s popular music for the people. It’s pop! My music might not be radio-friendly sometimes, but that’s just something we need to change. We hear the same thing all the time on the radio, which is not good. There are many influences in my music—jazz, funk, Congolese rhumba, electronic—but it is pop music. The thing about the world music category is that people won’t go there unless they want to discover new stuff. Something in the world music section won’t win Album of the Year, which I don’t understand, because there are some amazing albums stuck in there. There shouldn’t be any categories.

Your new album is called MAKANDA at The End of Space, the Beginning of Time. What exactly does it mean?

Well, ‘makanda’ means ‘strength’ in Chinoba. The reason why I called it Makanda is because I wanted to pay homage to the three women in my life: my mom, my aunt and my grandma. They each have the same values, but taught me different things in life. My mom always told me to be responsible and work hard, which is what I’ve always done. My grandma raised eight kids by herself after my grandfather died in the 1970s. That’s an example of determination. She raised them well and sent them all to school. And my aunt is the reason why my mom and I moved to Canada when I was 16. She’s probably the reason why I’m making music today. I don’t know if I’d be making music if I hadn’t moved here. She was a woman full of joy, always smiling with a joie de vivre. I decided to take my grandfather’s name for my stage name, and I believe he is living through me, like life is a circle.

How did you end up recording the whole album with Tendai Maraire from Shabazz Palaces?

A few months after my first album came out, I decided to reach out to Tendai and see if he would be willing to work on a few songs for my next album. Back then I didn’t have any idea of what I wanted to do, I was just a Shabazz fan and wanted to have a couple of songs with them on my next record. So we sent the album to Tendai and he wrote back saying we should come to Seattle to work on some stuff and see what happens. Then in May 2015 we travelled to Seattle for the first time and got to know each other a little. I said I was a big fan and wanted to work with him on a couple of songs. He had a few tracks that he thought would suit me, which he played me. I was inspired and we did the first track from the album, ‘Worlds of Solitude.’ The day we recorded that song, there was this magical moment in the studio. I don’t know exactly what happened but we looked at each other and said, ‘We need to do the whole record together,’ [laughs] and that was it.

You and Tendai were both born in Africa. Did that strengthen the bond between you?

Oh yeah, and we kind of have the same background. He is from Zimbabwe and moved to the States and grew up there. A similar thing happened to me, but I moved to Canada, and I grew up here. So we had the same struggle, because we both felt we had to fit in at some point. Though sometimes you decide to be yourself and do what best represents you, which is what we’ve both done. That’s what we tried to do with this record.

More content

Adsense